The Opium Wars were two devastating conflicts fought in the 19th century between China and Britain (later joined by France). At their core, these wars were about trade imbalances, imperial ambitions, and the devastating effects of the opium trade. What started as an economic dispute quickly turned into military domination, forcing China to open its doors to foreign powers in ways that would shape its history for the next century.

The Road to War: A Drug-Driven Trade Dispute

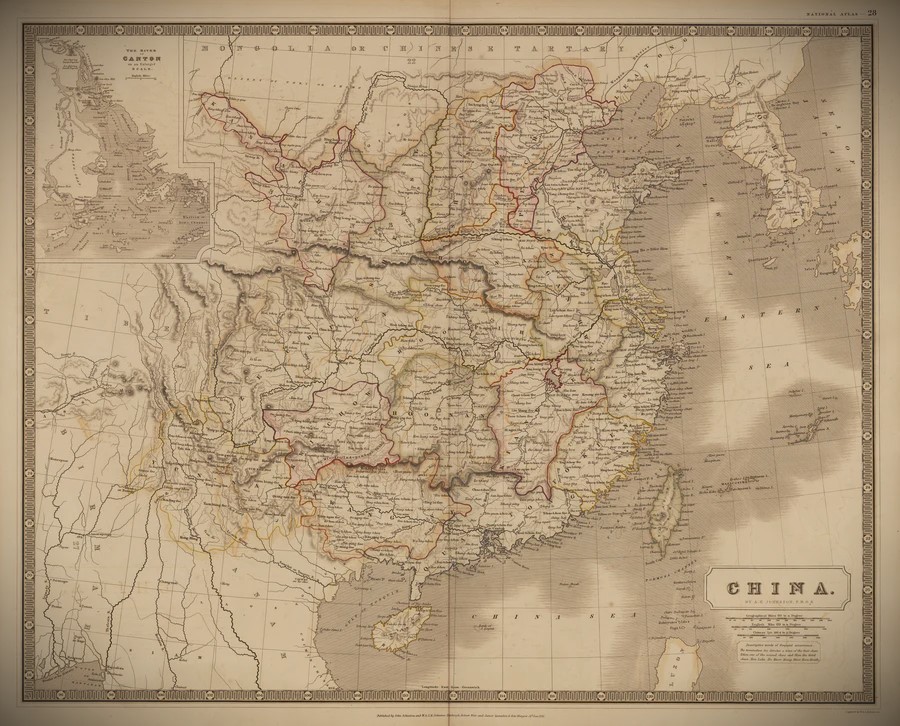

For centuries, China had been one of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful civilizations, exporting valuable goods such as silk, porcelain, and tea. However, China’s strict trade policies allowed foreigners to trade only through the port of Canton (Guangzhou) and required them to pay in silver, creating a massive trade imbalance—Britain was losing silver reserves while China remained self-sufficient.

To counter this, British traders—primarily through the British East India Company—began smuggling opium into China. Opium, derived from poppies grown in British-controlled India, was highly addictive, and demand soared. By the early 19th century, millions of Chinese citizens were addicted, including soldiers, officials, and common people.

China’s economy suffered as silver flowed out of the country, corruption increased, and opium dens became widespread. The Qing Dynasty, recognizing the threat, took a stand against the opium trade—setting the stage for war.

The First Opium War (1839–1842): China’s Defiance and Britain’s Cannons

The Spark: Lin Zexu Takes a Stand

In 1839, the Daoguang Emperor appointed Commissioner Lin Zexu to eradicate opium. Lin took an uncompromising approach:

- He arrested Chinese opium dealers.

- He seized and destroyed over 2.6 million pounds of opium in Canton.

- He wrote an impassioned letter to Queen Victoria, questioning Britain’s morality in pushing the drug trade.

Britain, whose merchants demanded compensation, used Lin’s actions as a casus belli (reason for war). The British government, seeing an opportunity to expand its influence and force open trade, sent its navy to attack China.

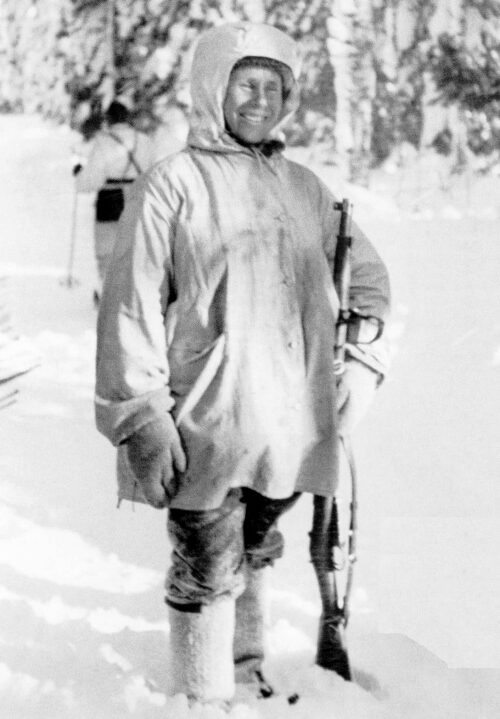

A One-Sided War

China, despite its size, was militarily unprepared for Britain’s modern warships and artillery. The British fleet, equipped with steam-powered ships and advanced cannons, devastated China’s coastal defenses.

Major battles included:

- Battle of the Bogue (1841) – British forces easily destroyed Chinese fortifications along the Pearl River.

- Battle of Chinkiang (1842) – British troops captured key cities along the Yangtze River, effectively cutting off vital trade routes.

By 1842, China had no choice but to surrender. The war ended with the humiliating Treaty of Nanjing, in which Britain forced China to open trade, cede Hong Kong, and grant extraterritorial rights to British citizens.

The Second Opium War (1856–1860): A Deeper Invasion

The Spark: The “Arrow” Incident

Although China reluctantly abided by the Treaty of Nanjing, tensions remained high. In 1856, a Chinese patrol searched a British-registered ship (the Arrow) for suspected smugglers. Britain, eager for more concessions, used this as an excuse to declare war again.

This time, France joined Britain, claiming that China had also mistreated Christian missionaries.

The War Escalates

Britain and France launched a full-scale invasion, not just attacking trade ports but marching into Beijing itself.

- In 1860, British and French troops captured Beijing, and in an act of cultural destruction, they looted and burned the Old Summer Palace, an imperial treasure trove of art and history.

- The Qing government, overwhelmed and humiliated, surrendered once again.

The resulting Treaty of Tianjin (1858) and Convention of Peking (1860) granted even more trade rights to foreign powers, legalized the opium trade, and gave Britain and France more control over China’s affairs.

The Aftermath: China’s Century of Humiliation

The Opium Wars left China in political and economic turmoil. The once-mighty Qing Dynasty was now at the mercy of foreign powers, who carved out spheres of influence in Chinese territory. This period, known as the Century of Humiliation, lasted until the early 20th century and fueled growing resentment toward the West.

Over time, these wars helped spark:

- The Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) – One of the deadliest civil wars in history, partly caused by Qing weakness.

- Growing anti-foreign sentiment that led to later uprisings like the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901).

- China’s modernization efforts, as later leaders sought to build a military and economy that could resist foreign domination.

Conclusion: A War That Shaped History

The Opium Wars were more than just military conflicts—they were a turning point in world history, symbolizing the clash between Eastern resistance and Western imperial expansion. Britain’s victory ensured European dominance over China for decades, while China’s defeat set the stage for political upheaval, revolutions, and its eventual resurgence as a global power in the modern era.

Even today, the Opium Wars remain a powerful symbol in China’s national memory, shaping its modern policies and its approach to foreign relations.